My early fiction tended to draw on familiar circumstances and settings. Rereading it, I persistently identify, sometimes vaguely, sometimes sharply, real life individuals who inspired characters. Usually, I recognize myself in the protagonist who reacts to events and interacts with other characters. "The Albatross," however, breaks away from that routine somewhat. To write it, I had to inhabit the personality of someone I assumed was essentially unlike me.

The main character, Dr. Stephen Coleridge Barclay, an aging English professor at a small college, is unhappily married, drinks heavily, and combats loneliness through affairs with co-eds. He's waiting in a hotel room above a bar for his latest lover to arrive and as he thinks about her, he remembers the first one who was his mistress for a long time before she graduated. Their relationship, though transient, was one each of them valued. In flashbacks Barclay fondly remembers their time together, believing her to have been more sincere, more committed, more compassionate than any of those who succeeded her. He struggles to convince himself that this new relationship might evolve like that first one. At the end of the story, as they prepare to have sex, his new mistress asks him to recite a poem, as if that will make the moment more romantic or at least temper his unease.

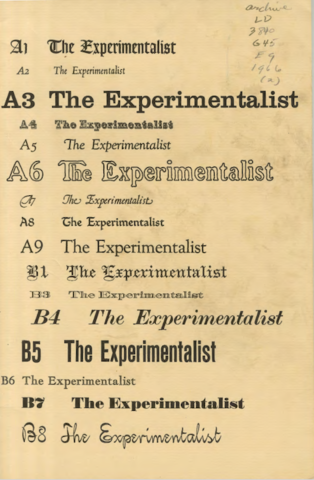

The short story has two literary allusions that try to deepen the sense of what the main character wrestles with. In the final scene of my typescript Barclay starts to recite Shakespeare's Sonnet 130, "My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun . . .", which the girl might possibly find romantic but the reader, having learned of Barclay's sense of her physical and intellectual shortcomings compared to his first lover, should find painfully ironic. In the version of the story published in The Experimentalist, our college literary magazine, Shakespeare's sonnet is replaced by Elizabeth Barret Browning's Sonnet 43, which begins, "How do I love thee? Let me count the ways," possibly a more direct address. Both sonnets are declarations of love, but the Shakespeare quote internalizes Barclay's misgivings more and Browning's emphasizes his conflicted hypocrisy.

Barclay's middle name, Coleridge, links him to the poet best known for "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner." Barclay's students and colleagues sometimes refer to him as that title character and, given not only his age but also his awareness of the dead albatross tied around the mariner's neck, Barclay also identifies with him. In my story, Barclay's albatross is entirely symbolic, a metaphor for his uncontrolled need for a young mistress, even one apparently accommodating but obviously insincere and not as genuinely affectionate as his first mistress. To convince himself to continue the affair, he tells her as he undresses, "You're no albatross. You're a bird of paradise."

When I wrote "The Albatross," I was a college student in my early twenties, sexually inexperienced, but somehow aware of a relationship between an older professor and a young woman I'd taken classes with. I'd been in one of his classes and knew his daughter, also a classmate of mine. When I reread the story, I can envision that man, that co-ed, the inn where their assignations take place, the streets of that college town. I'd taken good fiction writing courses there, in one composing fiction in the vein of Anton Chekhov and in both trying to inhabit the motives and the needs of someone other than myself. I must have given thought to the real-life situation of people I knew and wondered what would come of it. The story is essentially an attempt to imagine the psychological aftermath of such an affair on an aging teacher.

I published the story in The Experimentalist, probably assuming no one else would make the connection between fiction and real life. Several people did, and a few chided me for publicly exposing a relationship of which they too were aware. So, I was chagrined when my classmate who had been the real professor's lover approached me in the college center to talk about it. She and the professor had both read the story and discussed it together. To my surprise and embarrassed relief, they both felt I'd given a sympathetic and insightful reading of the future they faced. They knew they would break up when she graduated, and the professor dreaded her absence, his future emptied of the companionship she gave him. What would he do without her? Would he end up like Stephen Coleridge Barclay? I was pleased they thought me sympathetic.

I don't know what any reader who didn't know the background thought of the story. I know my classmate moved on; I don't know what the professor did. I think it may be the best story I ever wrote.

Notes: Bob Root, "The Albatross," The Experimentalist. Volume XII (Spring 1966): 39-45.

The Literary Magazine Project A Look at Geneseo's History Through Student Publications.